Book Review: Applied Ballistics for Long-Range Shooting, 2nd Edition

By Damon Cali

Posted on November 04, 2013 at 03:38 PM

I believe that a good understanding of ballistics will facilitate more effective long range shooting. That doesn't mean that shooters need to understand how to solve differential equations or know what a Magnus moment coefficient is, but it does mean knowing in general terms how bullets behave when they leave the muzzle.

Is wind more important down range or near the muzzle? What determines wind deflection, anyhow? Should we use heavy bullets and accept lower velocity, or use lighter, faster bullets? How much will those expensive Berger bullets help my High Power score? Knowing the answer to these questions will allow you to become a better shooter, as you can only go as far as your equipment - and knowledge - will take you.

Unfortunately, ballistics is a dense topic. High school (or even college) math is just not going to be enough to gain true understanding. Engineering tends to be that way, and ballistics is no exception. While you can learn a lot by reading Bob McCoy's excellent book, it's not for everyone. As much as I love that sort of detail, most people will just find it obscure and boring. It's an engineering text book, after all.

Speaking of Robert McCoy's book, I think he deserves a lot of credit for bringing the science of ballistics to engineers like me who do not have formal training or professional experience in ballistics. It's really the only accessible modern engineering text on the subject. That's a huge deal. Before McCoy, engineers with an interest in ballistics had to search for arcane papers and buy expensive old books written decades ago. It was very difficult to piece it all together because there was no A to Z overview. McCoy changed all that. At least, for engineers.

Just as McCoy brought ballistics to engineers, Bryan Litz brought ballistics to everyone else. That's a big statement, but I think it's earned. I've read just about every ballistics book on the market. Applied Ballistics for Long-Range Shooting is by far the broadest, deepest, and most accessible book on the topic, at least as it applies to sportsmen. There is very little math, but the concepts are still given a relatively full treatment, which is no easy task for an author.

There are three sections in the book. The first is an overview of ballistics theory and measurement practices, the second contains some ballistic analysis applied to some typical real life examples, and the third is a catalog of bullet drag data for popular long range bullets.

Part 1: The Elements of Exterior Ballistics

Chapter 1: Fundamentals

This is a quick chapter, and explains some very basic scientific concepts like the difference between accuracy and precision, velocity, and energy. It's a brief but necessary introduction for those who need a refresher on the high school physics they never thought they'd need.

Chapter 2: The Ballistic Coefficient

There is a lot of knowledge in Chapter 2. Bryan jumps right into discussion of what a ballistic coefficient is and isn't. The concept of a form factor and drag function are introduced. If you've wondered what the difference between a G1 and G7 drag function is, you'll find it in here. Banded ballistic coefficients are explained, as well as why they are not an ideal solution. Later in the chapter, the difficulties and uncertainties involved with measuring ballistic coefficients are explored. It turns out to be a lot of work to do properly. There isn't a lot of fluff in this chapter, but it's probably the most important one in the book, so keep studying until you get it.

Chapter 3: Gravity Drop

Bullets travel in arcs. In Chapter 3, the details of those arcs is discussed, as are the aspects we care about. The implications of zeros at different ranges is examined, and the concept of danger space is introduced. This is not a terribly difficult or interesting chapter, but builds out the necessary base for further understanding of a bullet's flight.

Chapter 4: Uphill/Downhill Shooting

When I first learned that shooting uphill has the same effect as shooting downhill, I was a little surprised. This will probably be the first counter-intuitive in this book, but it won't be the last. Bryan explains why this is the case in Chapter 4. It's a quick chapter, but full of good, practical knowledge that will leave you prepared to navigate angled fire.

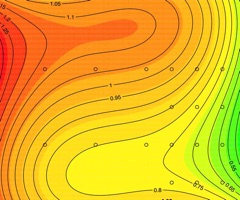

Chapter 5: Wind Deflection

This chapter is long. It has to be because it is the most useful one in the book. Understanding the behavior of bullets in wind is critical knowledge for an aspiring marksman. The mechanism that creates wind deflection is described (it might not be what you think). The concept of lag time and its relationship to the ballistic coefficient is introduced. Some subtle wind effects like wind gradients and the difference between near wind and far wind are explained. By the way, did you know that a pure cross wind will generate a vertical wind deflection in addition to the horizontal deflection? Strange, but true, and Bryan explains why and how this happens. The chapter wraps up with some practical wind reading tips as applied to various shooting disciplines.

Chapter 6: Gyroscopic Drift

Also known as spin drift, gyroscopic drift is the phenomenon where the spin of the bullet causes a sideways deflection. Often ignored because it is both small and consistent, it is nonetheless a real phenomenon that can and should be accounted for at long range. This chapter explains why it happens and how much it matters. Understanding when and how much to care about spin drift is another small piece of knowledge that will help you better concentrate on the task at hand - hitting the target.

Chapter 7: The Coriolis Effect

This is a quick chapter. It's also the least practical in the book. It turns out that the motion of the earth impacts the trajectory of a bullet. This very short chapter explains why that is. But in the end, this effect is very small for small arms, and as a result, any discussion of the Coriolis effect is solidly in academic territory. Still, it's interesting and worth the five minutes it takes to read.

Chapter 8: Using Ballistics Programs

This book will not tell you how to write a ballistics program, but it will tell you how to use one. This is a welcome chapter that explains the nature of ballistics calculators and their limitations. Uncertainty, correlation with real world results, and the concept of density altitude are discussed. The book also comes with a DVD that contains a point mass ballistics calculator. The point mass method is the current state of the art for our purposes, and the Applied Ballistics version is as good as any other.

Chapter 9: Getting Control of Sights

This chapter isn't really about ballistics. It's about a practical problem that you may or may not have thought much about - how good are your sights? Does a click really move the cross hairs as much as it should? Every time and in every position? What about cant? What happens to your signs if your rifle is tipped to the side a little? This chapter is all about setting up your sights and making sure you are getting what you think you are. It's a companion chapter to chapter 8 - once you have the results from your ballistics calculator, you must be able to translate those into the real world mechanics of your rifle. This chapter shows you how.

Chapter 10: Bullet Stability

Bullets are stabilized by spinning them very rapidly - as much as several hundred thousand rpm. This is a fairly detailed description of what is a fairly technical and nuanced topic. You'll learn all about the positive and negative effects of bullet spin, why we need spin, and why more is not always better. If you've wondered why .30 caliber 168 grain Sierra MatchKing bullets go crazy at about 800 yards, this chapter will explain it.

Chapter 11: Extended Long Range Shooting

This is really an extension of Chapter 10, and deals primarily with the stability problems that might be encountered at very long range (beyond 1000 yards), when bullet velocities drop into the dreaded transonic range. Dynamic instability is explored in some depth here, as well as some other effects that we typically ignore at mid and short range.

Part 2: Ballistic Performance Analysis

Chapter 12: Interesting Facts and Trends

Chapter 12 is sort of a grab bag of topics that don't fit in elsewhere. I also think it's one of the more interesting chapters, and gets into some deeper discussion. Among the topics discussed is the scalability of bullets - what is the effect of simply scaling up a bullet design? Also covered are kinetic energy and the causes of bullet dispersion.

Chapter 13: Example Performance Analysis

In addition to predicting where a bullet will hit, a knowledge of ballistics can aid you in choosing a caliber and bullet for a particular application. In Chapter 13, Bryan explores this topic from the perspective of an NRA High Power shooter by using some concrete examples. Along the way, yet more interesting knowledge is injected here an there, like the impact of bullet pointing and some commentary on the slow/heavy vs light/fast debate. There is a interesting statistical simulation that shows how much a different bullet might impact a shooter's High Power score. Reading it should cause you to relax a bit and concentrate on what matters.

Chapter 14: Generalized Score Shooting Analysis

Expanding on Chapter 13, this chapter contains more detailed analysis that quantifies the effects of ballistic performance on long range high power scores. In other words, it tells you just how much improvement you can expect if you shell out the extra cash for those fancy high-BC bullets. Using the same simulation techniques used in Chapter 13, Bryan explores the impact of ballistic advantage on High Power (including F Class) scores for novice, average, and elite shooters. I firmly believe that knowing what matters is half the battle of long range shooting, and this chapter contains that knowledge by the bucketload.

Chapter 15: Lethality of Long Range Hunting Bullets

I'll be honest. I don't get long range hunting and have no desire to do it. But if I were going to shoot game at long range, I would want to make sure that the equipment I used is up to the job. Chapter 15 delves into the energy required by various calibers and bullets to provide clean, humane kills. Just because you can hit the animal doesn't mean you should, and this chapter will help you figure out what your limits are.

Chapter 16: Hit Probability for Hunting

A companion chapter to Chapter 15, this chapter explores the probability of hitting your target in the context of hunting. Just as you have to make sure your rifle is up to the task of cleanly killing game, you also have to be confident in a clean hit. This chapter details the statistical concepts that will help you ensure that you are not taking unnecessary risks when hunting. Know what your gear is capable of and stay within it's boundaries. It's a short chapter, but it contains information that every responsible hunter should have.

Part 3: Properties of Long Range Bullets

Chapter 17: Anatomy of a Bullet

There are a lot of funny words used to describe bullets: boat tails, ogives (pronounced oh-jive), and meplats. Not only are they defined in Chapter 17, their impact on bullet design is explored. If you've ever wondered why bullets are not shaped like footballs, you will find some answers here. The difference between a tangent ogive and a secant ogive are explained, as is their impact on a bullet's performance. An introduction to meplat trimming and pointing can also be found in this chapter, although I would like to see more on the topic (Bryan, if you're reading this - more please!). It's interesting stuff to anyone who wonders why some bullets shoot better than others.

Chapter 18: Monolithic Bullets

Most bullets are copper jacketed lead. Some are solid, monolithic brass or copper. Often turned on lathes, these bullets have some unique advantages and disadvantages when compared with their traditional counterparts. This short chapter gets to the bottom of it, and walks you through the nuances of solid bullets.

Chapter 19: Using the Experimental Data

This chapter serves as the instruction manual for the drag data presented at the back of the book and offers some insight into a simple method to roughly predict the BC of a bullet based on it's geometry. It also provides some brief but helpful descriptions of the bullets that were tested.

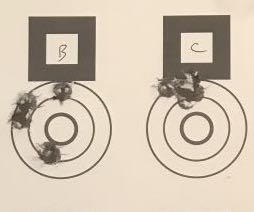

Experimental Data

One thing that becomes clear when reading the book is that the standard drag function used by most bullet manufacturers (the G1) is not as good a fit for modern long range bullets as the G7 drag function. But since almost nobody publishes G7 BC's, that bit of knowledge isn't very helpful. Bryan set out to change that by measuring the drag characteristics of a bunch of popular long range bullets. Not only are the G1 and G7 ballistics coefficients measured, but the uncertainty is outlined and you can see visually how well the data fits the standard functions. It's also nice to have a second set of data to support the manufacturers' stated ballistic coefficients. Incidentally, this is the data used by the Bison Ballistics ballistic calculator (with permission).

Appendices

Bryan skips almost all of the math in the body of the book. That's a difficult to pull off for such a technical topic and why the book is so good in my opinion. Still, there are some equations that are helpful to those who like math, and many are included in the appendices. You will not learn how to write your own ballistics calculator here, but you will learn the mathematical definitions of some concepts and how the Miller stability formula works, for example. It's not a text book, but a light overview of some of the simpler math that ballisticians tackle.

Overall Impressions

It should be clear by now that I love this book. It's perfect for the shooter how has gotten comfortable with the fundamentals and is looking for the next step in improving his long range abilities. Give it a read. You'll like it.

Damon Cali is the creator of the Bison Ballistics website and a high power rifle shooter currently living in Nebraska.

The Bison Ballistics Email List

Sign up for occasional email updates.

Want to Support the Site?

If you enjoy the articles, downloads, and calculators on the Bison Ballistics website, you can help support it by using the links below when you shop for shooting gear. If you click one of these links before you buy, we get a small commission while you pay nothing extra. It's a simple way to show your support at no cost to you.