F Class Basics Part 2: Ballistics and Reloading

By Damon Cali

Posted on March 05, 2020 at 08:02 AM

Note: The intent of this series pf articles to provide new shooters a basic understanding of the F Class shooting discipline as practiced within the rules set by the National Rifle Association. It will be assumed that the reader is familiar with basic firearms safety and marksmanship, and has at least read about basic reloading practices. This is not an advanced guide to cracking the top spot at Nationals. It’s a shortcut for new competitors to help get them up to speed — the hope being that a little knowledge can prevent a lot of frustration and wasted money.

I have tried to stay away from specific brands of equipment. While there are some pictures of typical gear in this article, don't take that as a recommendation.

The series is broken into two articles:

- Introduction and Equipment

- Ballistics and Reloading (this article)

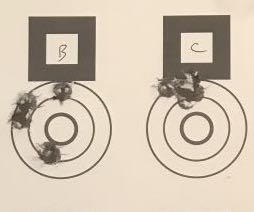

Precision Requirements for F Class

F Class is a precision rifle sport. There are no two ways about it - in order to be competitive, you need a very accurate, very consistent rifle. Consider that the X ring is about 1/2 MOA, and the 10 ring is about 1 MOA. A general rule of thumb is that in order to be competitive, you need a rifle capable of shooting 1/2 MOA for 20 shots. No flyers allowed. It’s not uncommon to see 600 yard Open class scores of 600-35x win matches. TR matches tend to top out in the high 590’s, but on a calm day, the best shooters will score a clean (200 out of 200) once or twice a day with the lowly .308 (or .223!). This article assumes that the reader is already reloading and is familiar with basic reloading. This section exists to point out some of the details that are pertinent to F Class shooters.

Brass

Consistency is the aim when picking brass. The high end brands like (Lapua and Peterson) dominate F Class. It’s pricey brass, but it’s good, strong, and consistent. There’s not much more to say about brass, other than to buy it in bulk, preferably all from the same lot. If you plan on shooting big weekend (or longer) matches, you will need several hundred pieces. If you're just up for some local club matches, 100 cases will do.

There is one note about .308 brass. Lapua makes a special match grade brass called “Palma” brass that is the same as their normal .308 brass, except it uses a small primer instead of a large primer. Peterson and Alpha Munitions have also started to produce high quality small primer brass.

Small primer .308 brass provides for improved ignition, higher safety margins, and greatly improved brass life. If you are shooting a .308, it's a is a no-brainer. The only downside is that erratic ignition can occur at very cold temperatures. This is not typically a problem at F Class matches, which tend to be in at least decent weather.

Bullets: Raw Accuracy Potential vs Ballistic Performance

When picking an F Class bullet, we have to balance a few factors: raw accuracy potential, wind resistance, and recoil. All three are required to shoot small groups at long range. Barrel life is also something to consider. Let's look at how these factors play out.

Short range benchrest shooters shoot short, stubby bullets through very slow twists and achieve amazing precision - group sizes that commonly dip well below 0.200" at 100 yards. The BC on these bullets is terrible, but the inherent accuracy is great. It turns out that the things that make bullets accurate are the things that make BCs poor and vice versa.

For F Class, wind resistance is of very high importance, so we use bullets that tend to be long and heavy - characteristics that provide for better drag performance, but hinder raw accuracy. These longer bullets tend to be more "finicky" than short range benchrest bullets. But we have to put up with that because if you don't the wind will kill your scores.

What this means in practice is that we need to select bullets that are low drag, but not to the point where the accuracy starts to suffer. This means we'll need match grade boattail bullets.

For .308 shooters, this means bullets in the 185-200 grain range. Those are pretty heavy bullets for the .308 case. Some shooters have tried to shoot even heavier bullets in F TR, but they seem to have fallen out of favor. I would advise newer shooters to start with a 185 class bullet, while more experienced shooters will do better with a 200 grain offering. Shameless plug: the Bison Ballistics 200 grain Claymore is designed specifically for F TR shooting and made to benchrest quality standards.

If you're going to shoot a .223, you must use a heavy bullet - a bare minimum of 80 grains if you want to be competitive. Ninety grain VLD bullets are the standard for competitive .223 shooters. These require a fast twist and careful reloading, but they are competitive with a .308 at 600 yards. Note that the 90s will require a very fast twist barrel, and are known to have issues blowing up in mid flight. Shooting 90s is very rewarding, but I would only recommend them for more advanced reloaders who are willing to set up a rifle specifically to shoot them.

For Open shooters, the advice is similar - use a bullet that is heavy for caliber with a high BC. Not too heavy or too high, or they won't shoot well. For a 7mm, that means something in the 180-185 grain weight class. Shooters of 6.5mm cartridges should go with a 130-140 grain bullet. If you're shooting a 6mm, you'll want to shoot something in the 103-115 grain range.

Ask around and you'll see some bullets come up more than others. That doesn't 'mean you have to shoot what everyone else is shooting to do well, but it might be a good place to start.

BC & Weight

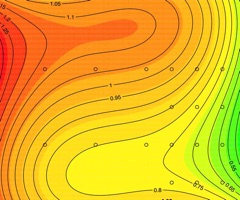

There are two ways to get good wind performance from a bullet. One is to use a design with a high BC. And the other is to add velocity. One way to add BC to a bullet is to increase its weight. But increased weight results in lower velocity. So is it worth it?

To a point, yes. Before you decide on picking a heavier, higher BC bullet, run the numbers through a ballistics calculator with realistic velocities. You may be surprised to find that adding weight (and BC) is a wash, or even detrimental to ballistic performance once achievable velocities are taken into account. And if we can avoid shooting heavier bullets, we should - heavier bullets have more recoil and are harder to control than lighter bullets. So run the numbers - don't assume heavier is always better.

One more note about weight: You will hear many shooters claim that if you fire two bullets of different weights, but with the same BC and at the same velocity, that the heavier one will give better wind resistance. This is not correct. BC already accounts for the bullet's weight. Wind resistance is determined by BC and velocity alone.

Powder & Primer

There isn’t much to powder and primer selection that is specific to F Class. Things to keep in mind are that in addition to good precision, your load also needs to have a high velocity, and very consistent velocity.

Measuring the variability of your velocity with a high quality chronograph is advised. Don't select a load based purely from chronograph readings, but do pay attention to them - poor velocity consistency is going to result in vertical stringing at 600 and 1000 yards. A load with a velocity standard deviation (SD) in the single digits is what you're after. Once you have that, let the target tell you what's good and what isn't - the best load is not always the one with the absolute minimum velocity SD.

Also, keep in mind that you’ll probably be shooting a rifle with a longer than “normal” barrel (typically 30") and very heavy bullets. That means the powders you select might be a little different from he ones you choose for your hunting rifles. QuickLOAD software is recommended as a valuable aid in selecting a powder, but it is not necessary. Ask around - chances are good someone else is using a combination of components similar to yours, and will provide a good starting point.

Load Development Process

This article assumes knowledge of load development, so we won't go into it here in detail. If you aren't already at an intermediate to advanced level of reloading, brush up on the topic. You'll want to look into the effects of varying charge weight, seating depth, and neck tension. You may also find that it's helpful to investigate ladder testing, and the concept of positive compensation.

Advanced Reloading

F Class matches are typically 60 rounds for record. That’s a lot of shots you need to keep inside 1 MOA in order to achieve a perfect score. It’s important to note that shooting a few 3-shot groups, noting that one or two are about 1/2 MOA does not mean you have a 1/2 MOA rifle. At least not in the sense that’s required for F Class.

A competitive F Class rifle requires rigorous load development that will result in a rifle capable of holding 1/2 MOA 5-shot groups every time.

That’s a pretty tall order, and one that can be discouraging for new shooters. But reloading is like any other skill to be learned. There are tricks and tips that can help make small improvements one step at a time.

Assuming you have a capable rifle, here is a list of topics you should look into if you feel like your reloading skills aren’t living up to your rifle’s potential. Experienced shooters will disagree on the effectiveness of these techniques, but they are all practiced to one degree or another by serious shooters.

Brass Sorting: Sorting brass by weight or capacity is something some shooters do to try to get more consistent internal case volumes, and hopefully more consistent velocities. Using high quality brass eliminates the need for a lot of this work, but even the best brass has variations.

Bullet Sorting: First and foremost, do not mix bullet lots. Bullets vary significantly from lot to lot (some brands more than others), and can have BC’s that change by as much as a few percent between lots. That makes a big impact on the target at long range. Even within a single lot, you will find bullets of varying length. Some brands need a little more sorting than others, but it doesn’t take long to do and is worth the effort.

Bullet Trimming and Pointing: Due to manufacturing methods, bullets come out of the box with a tip that is a little ragged (inconsistent) and is a shape that isn't quite optimal. There are two operations you can perform to help this condition. The first is trimming, which is just using a special trimming tool to trim the ragged part of the meplat (bullet tip) back slightly, increasing length consistency. However, trimming the bullet increases the size of the meplat and shortens the bullet, which increases drag. So some shooters run the trimmed bullets through a pointing die to close the tip back up and form the tip into a more optimal shape.

Neck Turning: Even good brass has a variable neck thickness. It’s not uncommon to find brass that is 0.001" thicker on one side of the case than the other. That may not sound like much, but when you're sizing a neck down just a few thousandths, it' matters.This eccentricity is a hindrance when it comes to consistent seating force, and to starting the bullet into the lands as straight as possible. Shooters have found that neck turning can increase the uniformity of case necks for more consistent sizing. There are lots of ways to turn necks, from hand held tools to full-sized lathes.

Chronographs: Maintaining consistent velocities is an important part of long range shooting. If velocity varies too much, your groups will grow taller as range increases. So keeping an eye on velocity is something worth doing. One thing to note is that not all chronographs are created equal. The cheaper optical models can be more trouble than they’re worth, and many aren’t capable of measuring as accurately as we required. The Magnetospeed attaches to your rifle’s barrel and is very accurate and convenient. However, attaching a weight to the end of the barrel can influence how it shoots, so they’re not advisable during load development. The Labradar is also very accurate, and perhaps even more convenient as you don’t need to set it up down range or attach it to your rifle.

Internal Ballistics, Custom Chambers & QuickLOAD: When trying to get the most ballistic performance out of your rifle using heavy bullets in long-throated chambers with longer than normal barrels, you will eventually figure out that reloading manuals don’t give you quite the information that you need. QuickLOAD is a program that calculates internal ballistics based on cartridge and barrel dimensions, bullet properties, and the propellant used. It’s a very helpful tool when operating at the edge of reloading data, and can be an indispensable tool for keeping pressures at safe levels while getting the most out of your specialized equipment. It has a bit of a learning curve, but it’s not terribly difficult to work with, and has a detailed instruction manual. The cost is about what a few reloading manuals would run, but it’s worth quite a bit more. QuickLOAD is a Windows program, but if you use an Apple computer, you can run it using emulation software like Crossover.

Damon Cali is the creator of the Bison Ballistics website and a high power rifle shooter currently living in Nebraska.

The Bison Ballistics Email List

Sign up for occasional email updates.

Want to Support the Site?

If you enjoy the articles, downloads, and calculators on the Bison Ballistics website, you can help support it by using the links below when you shop for shooting gear. If you click one of these links before you buy, we get a small commission while you pay nothing extra. It's a simple way to show your support at no cost to you.